Response

Introduction

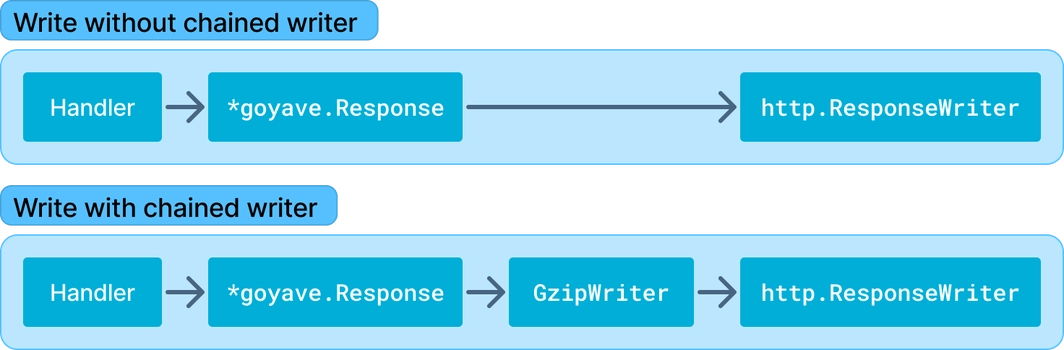

*goyave.Response implements http.ResponseWriter. This wrapper controls the response flow and brings a number of convenient methods to write HTTP responses. All writes first go through the *goyave.Response, even when using chained writers.

Pre-writing

PreWrite is an operation always called before any Write. Because the HTTP headers must be written before the response body, a write will automatically send them to the client. *goyave.Response uses this hook to make sure that the correct status code is written instead of the default 200 OK. This way, you can define a status code using response.Status() without sending the response header immediately. The status code can then be read by middleware and status handlers to process a dynamic response, even if the headers are not yet written.

Writing responses

You can set the status without immediately writing the response headers. This differs from response.WriteHeader(), which writes the response header. It is recommended to use response.Status().

response.Status(http.StatusUnauthorized)INFO

Calling this method a second time will have no effect.

response.JSON() marshals anything given to it into JSON, adds the Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8 header automatically and writes the response. Alternatively, if a simple string is enough, response.String() will work for you:

response.JSON(http.StatusOK, someDTO)

response.String(http.StatusOK, "Hello world")You can write files from any file system implementing fs.StatFS with either response.File() (which will send the file as "inline") or response.Download() (which will send the file as attachment).

import (

"embed"

"goyave.dev/goyave/v5/util/fsutil"

)

//go:embed resources

var resources embed.FS

//...

fs := fsutil.NewEmbed(resources)

response.File(fs, "resources/img/logo.png")

response.Download(fs, "resources/manual.pdf")You can also write to the response the standard way using Write():

response.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

_, err := response.Write(bytes)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}INFO

As opposed to response.JSON() and response.String(), response.Write() can be called multiple times. It can be used for streaming large responses to the client, and supports usual io helpers such as io.Copy().

Unsupported features

Because it is not the focus of the framework, certain rare use-cases are not covered, such as rendering templates and redirects. Because *goyave.Response implements http.ResponseWriter, you can still use it as a regular writer:

import (

"html/template"

"net/http"

"goyave.dev/goyave/v5"

"goyave.dev/goyave/v5/util/errors"

)

//...

// Redirect

http.Redirect(response, request.Request(), "/target", http.StatusPermanentRedirect)

// html template

tmpl := template.Must(template.ParseFiles("layout.html"))

data := map[string]any{

//...

}

err := tmpl.Execute(response, data)

if err != nil {

response.Error(errors.New(err))

return

}Error handling

When an error is brought back all the way up to the controller, you can handle it gracefully with response.Error(). This method will log the error and set the response status to 500 Internal Server Error. If debugging is enabled (config app.debug) and nothing has been written to the response yet, the error message will be written to the response body as well.

response.Error(err)WriteDBError() allows you to more easily handle database errors. It takes an error and automatically writes HTTP status code 404 Not Found if the error is a gorm.ErrRecordNotFound error. It calls Response.Error() if there is another type of error. This method returns true if there is an error. You can then safely return in you controller.

func (ctrl *ProductController) Show(response *goyave.Response, request *goyave.Request) {

product := model.Product{}

result := ctrl.DB().First(&product, request.RouteParams["id"])

if response.WriteDBError(result.Error) {

return

}

response.JSON(http.StatusOK, product)

}TIP

Learn more about the preferred error handling approach in the dedicated section

Chained writers

It is possible to replace the io.Writer used by the *goyave.Response. This allows for more flexibility when manipulating the data you send to the client. It makes it easier to compress your response, write it to logs, etc. You can chain as many writers as you want.

Usually, the response's writer is replaced in a middleware. The current writer is taken from the *goyave.Response, and used as destination for the newly created chained writer. This new chained writer is then set in *goyave.Response.

Chained writers are components, just like middleware and controllers. They can compose with goyave.CommonWriter, a structure that implements all the basic methods a chained writer must implement: goyave.PreWriter, io.Closer and goyave.Flusher.

Note that at the time a chained writer's Write() method is called, the request header is already written. Therefore, changing headers or status doesn't have any effect. If you want to alter the headers, do so in a PreWrite(b []byte) function (from the goyave.PreWriter interface).

The writers are closed at the end of the finalization stage, telling them that the application is entirely done with this request.

The following example is a simple implementation of a chained writer and its middleware for logging everything sent by the client:

import (

"io"

"goyave.dev/goyave/v5"

"goyave.dev/goyave/v5/util/errors"

)

type LogWriter struct {

goyave.CommonWriter

response *goyave.Response

body []byte

}

func NewWriter(response *goyave.Response) *LogWriter {

return &LogWriter{

CommonWriter: goyave.NewCommonWriter(response.Writer()),

response: response,

}

}

func (w *LogWriter) Write(b []byte) (int, error) {

w.body = append(w.body, b...)

n, err := w.CommonWriter.Write(b)

return n, errors.New(err)

}

func (w *LogWriter) Close() error {

w.Logger().Info("RESPONSE", "body", string(w.body))

return errors.New(w.CommonWriter.Close())

}

type LogMiddleware struct {

goyave.Component

}

func (m *LogMiddleware) Handle(next goyave.Handler) goyave.Handler {

return func(response *goyave.Response, request *goyave.Request) {

logWriter := NewWriter(response)

response.SetWriter(logWriter)

next(response, request)

}

}You can override the default behavior of PreWrite(), Close() and Flush(). If you do so, make sure to call the CommonWriter's implementation so the writers are correctly chained for these operations:

func (w *Writer) PreWrite(b []byte) {

//...

w.CommonWriter.PreWrite(b)

}

func (w *Writer) Close() error {

//...

return errors.New(w.CommonWriter.Close())

}

func (w *Writer) Flush() error {

//...

return errors.New(w.CommonWriter.Flush())

}INFO

Chained writers support both http.Flusher and goyave.Flusher for their underlying writers. The only difference between those interfaces is that http.Flusher's Close() method doesn't return an error but goyave.Flusher's does.

Hijack

Goyave responses implement http.Hijacker. Hijacking is the process of taking over the connection of the current HTTP request. This can be used for example for websockets.

Middleware executed after controller handlers, as well as status handlers, keep working as usual after a connection has been hijacked. Callers should properly set the response status to ensure middleware and status handler execute correctly. Usually, callers of the Hijack method set the HTTP status to http.StatusSwitchingProtocols. If no status is set, the regular behavior will be kept and 204 No Content will be set as the response status.

Writing to the *goyave.Response after being hijacked should be avoided as it would cause an error. Therefore it is advised to always check if the connection was hijacked (using Response.Hijacked()) before writing anything when inside a middleware that has operations executed after the controller handler. Calling response.Status() after a hijack is safe but won't have any effect.

After a call to Hijack, the original request body reader must not be used. The original request's context.Context remains valid and is not canceled until the end of the request lifecycle.

Chained writers are not discarded when a connection is hijacked, and will still be closed as usual at the end of the request's lifecycle.